Money on the PGA Tour: Contextualizing Tiger Woods’ 82nd Career Victory

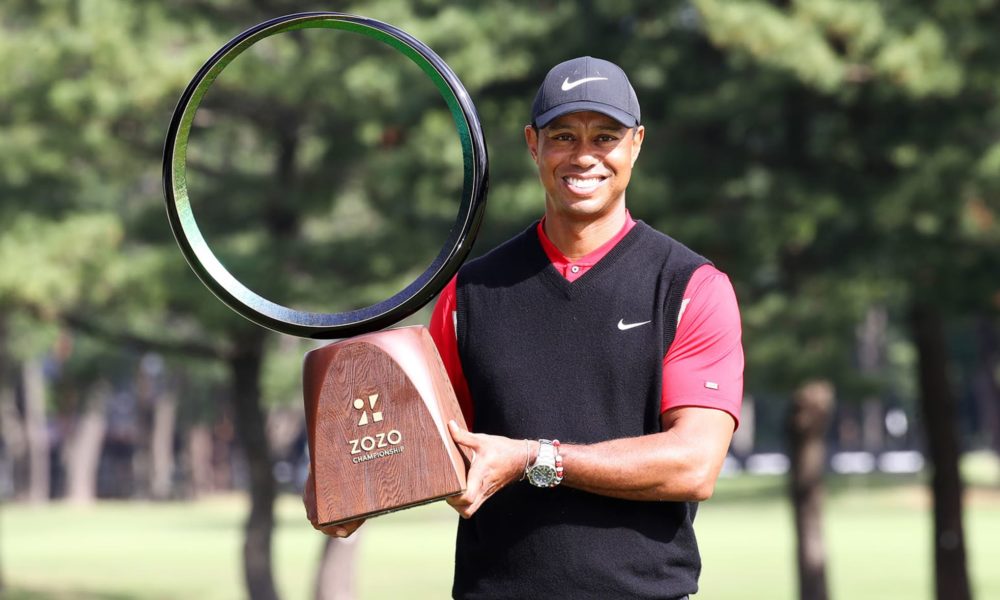

At the inaugural Zozo Championship this week outside Tokyo, Tiger Woods captured his 82nd PGA Tour victory, tying him with the legendary Sam Snead for the most wins all-time since the Tour was founded in 1929. The tournament itself was unique, in that it was the first Tour-sanctioned event in Japan amidst the season’s “international swing” which includes stops in Mexico, Bermuda, South Korea, and China. The Presidents Cup will take place in Australia this December and golf will return to the Summer Olympics in Tokyo for 2020 as well. In recent years the PGA Tour has shaken up its schedule, emphasizing international events particularly as it struggles to compete with the beginning of the NBA/NHL seasons and the heart of the NFL regular season back in the United States.

With a greater international presence and larger TV/marketing deals on the horizon, advertisers have flocked to the PGA Tour, especially with officials lifting a ban that now allows players to be sponsored by liquor companies, gambling sites, and daily fantasy enterprises.

Sam Snead won his first PGA Tour event, the West Virginia Close Pro, in 1936 at Old White TPC at the Greenbrier Resort in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia. Over the course of his 82 PGA Tour victories, he earned a total of $620,000[3]. Adjusting for inflation from his last victory (1965 Greater Greensboro Open), his career earnings come to $5.13 million. In contrast, Tiger Woods has made over $120 million over the past 23 seasons. Just his 80th (2018 Tour Championship), 81st (2019 Masters) and 82nd (2019 Zozo Championship) victory alone amount to nearly $300k more than Snead’s adjusted total earnings over his career. Why the growth in prize money over the past 2 decades? Roger Pielke Jr. of the University of Colorado has dubbed the phenomenon “The Tiger Effect” after analyzing PGA Tour event purses from 1990 to 2014. He found that in the seven seasons prior to Woods joining the Tour, the prize pool on Tour grew at a rate of approximately 3.5% annually. Since 1997 when Woods emerged on Tour, that number now averages 9.3% of growth, nearly three times the rate just a few seasons earlier.

Pielke adds that Woods isn’t the sole beneficiary of the added money in golf either- when he looked at the earnings of the top players from 1997-to 2008, he found that many stars, from Vijay Singh and Phil Mickelson to Ernie Els and Sergio Garcia, could all attribute more than half of their earnings over that time frame to event purses inflated from said “Tiger Effect.” Conversely, following Woods’s fall from grace after a 2009 car crash and cheating scandal, purses decreased by 2.3% in just one year. While Woods had an injury-plagued stretch following his 2013 five-win season, his recent successes are a bright spot for the PGA Tour. When Woods won the 2019 Masters, CBS announced that it was “the highest-rated morning golf broadcast in 34 years.” Granted, most golf events are broadcasted in the afternoon, but organizers were forced to push the event earlier due to weather. As Tiger was finishing his championship final round, the telecast commanded 28% of total viewership across the country- an impressive feat for any sports event let alone a rescheduled golf tournament.

The growth of golf marketing actually began in the 1960s, due largely in part to attorney Mark McCormack. McCormack, a Yale Law graduate, was working at Arter & Hadden in Cleveland when he began organizing single-day golf tournaments. It was there that he developed the idea of a sports agency “firm”, and shortly thereafter founded International Management Group (IMG). He signed star golfer Arnold Palmer as his first client and immediately began marketing him in a new way. Rather than focusing strictly on golf equipment and apparel, McCormack had Palmer serve as an “ambassador” for a variety of companies- from Coca-Cola to Cadillac, dry cleaning chains to blood-thinning medication. Before McCormack, Palmer’s annual off-course earnings were estimated at just $10,000 at the end of the 1950s. Just two years after signing with IMG and winning two major championships, that number reached over $500,000 per year. Despite not winning a PGA Tour event since the 1973 Bob Hope Desert Classic, Arnold Palmer ranked 9th in the 1990 Inaugural Forbes Richest Athletes list, which excluded his income from golf designing. Athletes making more money off the field than on it is no surprise either- Tiger Woods’ career earnings top out at over $1 billion despite making less than 15% of that from prize money in tournaments. The McCormack marketing model paved the way for athletes and endorsements years later, including players like Michael Jordan, Derek Jeter, and LeBron James.

Sports agencies and lawyers have been an integral part of the economic growth in sports. Their advocacy efforts have strengthened bargaining power for athletes, helped pave the way for free agency, and expanded the voices of athletes beyond the field. And while lawyers are often in the background as athletes take the podium or hit the field, the power of knowing the law and having practical business strategies have helped grow sports from spectator events to culturally immersed spectacles that have given athletes and their organizations a platform to discuss more than Xs and O’s. Tiger Woods’s victory in Japan is more than just a record-breaking feat. It is the culmination of a half-century of growth in the game of golf and in professional sports as a whole. While Sam Snead would admire the fortune Woods and many more have made throughout the past few decades, the true accomplishment that Snead would smile at is the growth of the game and excitement that Tiger has brought to a sport that was traditionally regarded as just a respectful, country club activity for society’s richest.

Read More: Analyzing the Proposed MLB Rule Changes